Stone Heads

Around Europe, what are commonly referred to as ‘stone heads’, are frequently found, often in areas that are known to have been lived in by Celts. In one place in the UK, over 2000 have been found and these are thought to have all been carved by the same tribe. Stone heads are effectively stone carvings of heads and are thought to have been made as if in place of severed heads, which are known to have been collected by some Iron Age Celts and displayed as trophies in their houses or temples, as well as depicted in some of their art.

Heads were revered in the Iron Age and were deemed much more valuable and precious than any of the other bones or body parts. The Iron Age Celts called the head the ‘seat of the soul’ and believed that they had the ability to turn aside evil and bring about good fortune. It is also thought that there is a relationship between religious practices and the carving of stone heads, explaining perhaps, why these carvings were often displayed in the Celts’ temples.

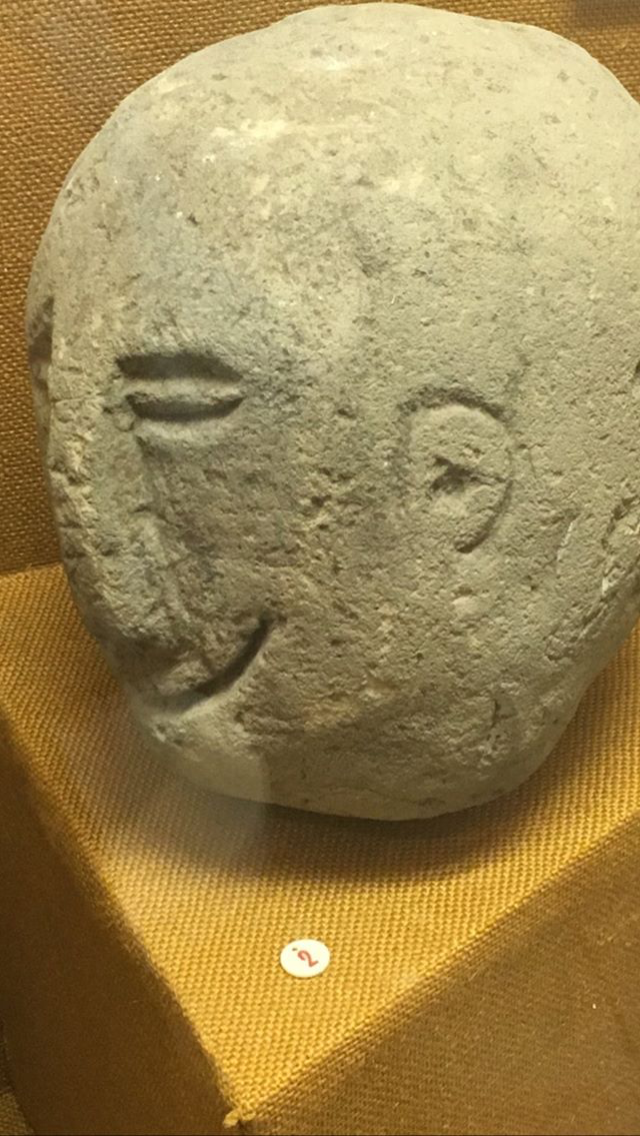

Iron Age stone heads usually have a set form of features: they are simple; have a flat face and nose; close-set, sometimes heavy-lidded, lentoid eyes; abstract features; a lack of facial expression; an elongated head; and slit mouths. Their simplified faces have often been thought to evoke “the stern and brooding presence of an Otherworld being” (Raftery, 186).

The late Barry Raftery was an Irish archaeologist and Celtic scholar who was known for his work on the Iron Age in Ireland. His internationally distinguished career was regarded by many as having a major impact on archaeology at both an Irish and European level, as well as being an inspiring and communicator in his rôle as the chair of Celtic archaeology at University College Dublin.

Celts are often somewhat crudely referred to as ‘head hunters’ and despite the fact that they did collect severed heads, this phrase doesn’t cover the respect and veneration with which they regarded them. However, the act of severing a head wasn’t just to disrespect a fallen enemy, often the heads of allies killed in battle were collected, to keep it from falling into the wrong hands. The concept of the head containing the soul stemmed from this practice as the Celts believed that if the head remained, so did the person, through their soul.

Iron Age Celts worshipped their many gods and goddesses through practices such as sacrifice and it is thought that to collect heads was an interpretation of this. It also may have been believed that the head of a fallen foe would be beneficial to the taker of their head or a thanks to the gods and goddesses for bringing prosperity and a good harvest to their family and lands.

The actual existence of the so-called Iron Age Celt ‘head cult’ is debatable, but it can be agreed that the reverence, symbolism and favour placed upon the head motif by the Celts shows that, at the very least, a certain spiritual belief and respect was required if one managed to find themselves in possession of a human head.

The human heads they collected were preserved using conifer resin, resulting in embalmed heads that could be displayed without them rotting or decaying. Scientists think the method of covering the heads in resin could have been either dipping them in it or having it poured over, and that this process may have been repeated several times over the head’s ‘afterlife’. In France, the heads were believed to have been displayed at the front of the victor’s house ‘as trophies to increase their status and power, and to frighten their enemies’ (source: Live Science).

Apart from possessing a large amount of what could almost be described as backstory, the Iron Age Celt stone heads are really just fun. They comprise a wealth of historical fact for someone to discover; the blood guts and gore everyone pretends to hate; and a barely-there smile that captivates the viewer. There is simply something about these carvings that never fails to bring a smile to my face or pique my interest in their history. I am only too glad to be able to share my fascination with stone heads and I hope that at least one aspect of their many intriguing features manages to seize your attention and inspire you to learn more.

Sasha Minnis