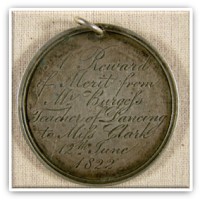

Silver school prize medal inscribed Mrs Elliott’s Ladies Boarding School, Devizes on one side and A Reward of Merit from Mr Burgess, teacher of dancing to Miss Clark, 12th June 1822.

Silver school prize medal inscribed Mrs Elliott’s Ladies Boarding School, Devizes on one side and A Reward of Merit from Mr Burgess, teacher of dancing to Miss Clark, 12th June 1822.

Frances Elliott (1782 – 1860) was a governess and teacher, running schools for young ladies – first in the High Street, and by 1841 at 41 Long Street, which now forms part of the Museum.

Frances was married to Rev Richard Elliott (1781 – 1853) who came to Devizes in the early 1800s. He was pastor of the Congregational Church in the town for 50 years and an important figure in Congregationalism.

No. 41 must’ve been a very busy household! The 1841 census records the occupiers as Frances Elliott, four of her daughters, 33 female pupils (aged 4 to 19) and two female servants. Whilst it is a large building, we can only guess at how they all lived, slept, cooked, eat and studied …… and a lot of work for the two servants.

Fanny and Richard’s daughters – Eliza, Mary, Charlotte and Jane – were all teachers or governesses at some point in their life. Their eldest daughter, Rebecca Anne, married Robert Waylen Jnr, and continued educating pupils in Devizes, including her own children, and later, as a governess with boarding pupils in Northgate Street.

Lorna Haycock, our former Librarian and Archivist, gave a lecture in 2012 about Georgian and Victorian Schools. Her lecture notes are below:

GEORGIAN AND VICTORIAN PRIVATE SCHOOLS IN DEVIZES

Today we expect education to deliver answers to various social problems and to galvanise the youth of this country into striving to fulfill their full potential. Yet this was not always so in the past. Education was thought of as a limited tool. It was useful as a way of keeping the masses under control by religious indoctrination, but it was thought that too much learning would make them restless and develop ideas above their station. It was also regarded as a means to a commercial end, to train clerks who could contribute to the growing prosperity of the country at a time of industrial change.

Since 1870, we have in this country gradually built up a national system of education arranged in tiers at primary, secondary and university levels. But before that process began, the provision of education was haphazard and largely supplied by private or religious bodies. The majority of working class children attended no school, either because there was no provision of education or because they were expected to contribute to the family income. For the poor, charity provided the only chance of education, the main aim object being to establish social discipline, to keep the poor in their place as ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’. In the late seventeenth century, funds were provided for the schooling and clothing of poor boys and girls and the employment of teachers at a site in Maryport Street, Devizes (where the old post office is now) and this site was later used by the Bear Club School. Members of this club established a fund , using the attendance fees and fines for non-attendance at their weekly meetings at the Bear Hotel to provide education, clothing and apprenticeships for poor town boys. Subsequent benefactors also enabled poor girls and boys to have a limited education. Instruction was confined to the 3Rs and ‘such branches of education as are necessary for servants’, with great emphasis on moral and religious instruction. One writer claimed that ‘to go further would confound the ranks of society’.

But farmers who did not want their children to attend the village or charity school sent them to board at educational establishments in Devizes during the week, so in the eighteenth century, a two class educational structure came into existence, with the foundation of private schools to provide moral, social and practical education for the middle class. Boys were taught the 3Rs and merchants’ accounts to fit them to be clerks or traders. One school proprietor, the Reverend B. Morgan advertised that he trained his pupils for the ‘University of Trade’. The practice of sending girls to school was growing among the middle class, to teach them social deportment and prepare them for their role as the wives of merchants, clergymen and superior shopkeepers. Women were targeted by publications such as ‘The Lady’s Monthly Museum’ (which we have in our Library), containing book reviews, poetry and sections on female interests. Teaching, an extension of the maternal role, was one of the few employment avenues open to women, but few had any formal training or qualifications. Thomas Trotter claimed that ‘any lady of tolerable mediocrity, talents and accomplishments who can win the countenance and support of a few well meaning friends in the neighbourhood is deemed equal to direct a boarding school for young ladies’.

Many advertisements for girls’ schools stressed strict attention to morals. Girls were not taught mathematics or science and the curriculum was usually confined to feminine subjects and the social graces, needlework, dancing, music, French and English. The economist Adam Smith thought the purpose of women’s education was to ‘improve the natural attractions of their person— and to render them both likely to become mistresses of a family and to behave properly when they become such’. Another contemporary observed that ‘ Miss Stay-Tape, The Taylor’s daughter, is taught to walk a minuet and dance a cotillion with the hopes of attracting some man in a superior rank of life to herself’. Although girls’ education tended to reinforce social and gender distinctions, the smattering of education and the growth of circulating libraries purveying novels and romances helped to increase female literacy and disseminate ideas.

Some boys’ private schools were run by Nonconformist ministers to augment their income. One of the leading boys’ school in Devizes was the Presbyterian Rev. Fenner’s Grammar School here at 40 Long Street, which was attended by Thomas Lawrence , the later artist who may have sat in what is now our Library. We know something of life at the school from the diary of Fenner’s nephew, Henry Crabb Robinson, who spent three years there from 1777 to 1780. A writing master and a French teacher ‘ of the University of Paris’ were employed along with a visiting dancing master from Bath to instruct the 40 pupils from Devizes and neighbouring clothier families in Wiltshire. Once a month parents were invited to see their sons dancing and on Whit Monday a ball for pupils was held in the Wool Hall. At dancing lessons the boys were partnered by girls from Miss Edwards’ school next door at number 41, but we are told that ‘some outrage occurred’ which resulted in segregation of the sexes, so in future the young ladies had dancing on Mondays, and the boys on Thursdays. A fagging system operated at the school and the boys were charged half a crown for broken windows.

Domestic arrangements were run by Mrs Fenner, who in the words of one of the pupils was ‘ as good a soul as took snuff and not a little of it’. Breakfast for the boarders consisted of bread and milk- tea was a guinea a year extra. Pudding and meat were provided for dinner. Sunday lunch consisted of rice pudding made from skimmed milk, water and brown sugar, boiled then baked, and a large round of salt beef. On Mondays the boys had soup, augmented in the winter by thick veal. Tuesdays they were served boiled figgy puddings made from flour, water and suet, with cold beef; on Thursdays they had rice pudding and roast veal, Fridays they were served liver and sheeps lights, and on Saturday the beef and veal left over from the roast were put in 2 large pewter dishes, covered with pastry made from flour and tallow and baked in a local bakehouse. Boiled potatoes came from Fenner’s garden at the back of the property. Grace was said at meals, lasting ten minutes before the meal and a quarter of an hour after, but strangely there was no religious instruction.

Increasingly, private schools became extremely competitive. To rise in the commercial hierarchy involved the acquisition of social graces and the trappings of genteel status. Schools competed fiercely for custom, employing advertisements in the Salisbury Journal and the Devizes Gazette to stress the superior education they could offer. At Mr Anstie’s school, boys could learn ‘The Elements of Natural Science, Mechanics and Geometrpy’, though this raised the fees to 22 guineas a year. After the French Revolution, French exiles turned to teaching; Mrs Duck boasted ‘a French assistant‘ and a Frenchman featured as dancing master at Miss Edwards’ school.

During the nineteenth century, the number of private schools increased- at least 16 houses in Long Street at various times were occupied by private schools- numbers 8, 11, 14, 18, 27, 30, 35, 36, 38, 40 , 41 and 45. We must remember that most of these houses were spacious, dating from the eighteenth century, and offered room to take in boarders, from whom much money could be raised. At 41, Mrs Elliott, wife of the Congregational minister ran a ‘high class school for young ladies’, where some of the young ladies evidently whiled away their time by carving the date on the banisters on the first floor – May 4 , and then three strokes Richard Biggs, son of Baptist minister James Biggs, started a school at Lansdowne House, where the imposition of fines for bad behaviour formed the basis of instruction in book keeping. At number 35 Long Street, Rev. George Bricknell kept ‘ a high class school for the sons of gentry and clergy’. Wilsford House School at number 30 Long Street, founded in 1888 where the Conservative Club is now, was one of the most popular. It was run by DGW Rumsey, described by one of his pupils as ‘a booming, black bearded figure who deflated considerably when faced on one or two occasions by an irate parent’. One of the Assistant masters had an Honours degree in History from the University of Wales, music was taught by Harry Baker, the parish organist and drill was supervised by Staff Sergeant Bailey of the Grenadier Guards. Masters at this school used the ruler to preserve discipline, but stubborn cases of bad behaviour would be sent downstairs by the teachers to Rumsey himself, afterwards to emerge chastened both in body and appearance. The school had 15-20 boarders, whose parents paid 30 guineas a term; day pupils were charged 6 guineas. The boys, aged between 8 and 16, wore black mortar boards with black and yellow tassels on Sundays. They were accommodated in 2 large houses including 2 well ventilated rooms with classrooms attached and special attention was paid to sanitary arrangements Mrs Rumsey was described as a ‘kind, gentle woman, obviously cowed by her husband’. The school had a gymnasium and a large playing field, in the area now occupied by the Bowls Club and the Scout Hut. Classes numbered 30-40 pupils, who were taught a little bit of everything although in theory they could be prepared for London University Matriculation, the College of Preceptors’ and professional exams. They had to learn by heart a short passage of Scripture each evening in addition to normal homework. The school had shrunk by 1911 and the girls department, at 27 Long Street, where the ambulance garage is now, was closed. Rumsey was occupying himself touring the countryside giving lectures on tariff reform, the great political issue of the day.

In 1859, a joint stock company was established by Devizes residents to set up a Proprietary Grammar School here, sandwiched between 40 and 41 Long Street, and you are now sitting in one of the Victorian classrooms; the Library forms the other classroom. Outside the back door of the museum are some initials probably carved by some of the pupils. The school had failed by 1871 and these rooms were purchased by the Society in 1872 for £620, though a further £300 was necessary to fit the premises out for the Museum and Library. The title of the Grammar School was taken over by the Pugh family elsewhere in the town. The New Baptist minister, S S Pugh, started the school at 3, Lansdowne Grove in 1871, and then moved to Heathcote House on the Green in 1874, where he was followed as Headmaster by his twin sons, C W Pugh and C S Pugh. Their sister ran a girls’ department from 1911. The boys’ school aimed to ‘produce honourable and useful men’ and gave a thorough business education, including book keeping and shorthand. Outdoor recreation was encouraged and a large field was available for football and cricket. In our Library postcard collection, we have a postcard addressed to E.Gillman, which reads ’We played Mr Pugh’s Grammar School and they beat us 3 to 1, but two of their goals were offside’. But it was a well rounded school: a resident later wrote ‘The teaching and training I have had from Mr Pugh I have remembered all my life- I often think during my daily work of what Mr Pugh taught me’

Another popular school was situated at Verecroft in Long Street established in 1858. In 1900 under its Principal, Mrs Holbourne, it took 18 boarders as well as day pupils, from the ages of 5 to 18, although there was a kindergarten for 3 to 7 year olds, this being described as ‘ a golden bridge between home and school’. There were special terms for brothers and for Anglo-Indian families, and delicate or backward children were particularly catered for. Teaching took the form of lectures in Scripture, English Language and Literature, History , Geography , Mathematics and Natural Sciences and there was also instruction in Book-Keeping and Needlework and musical and other drills. Extras included French, German, Latin and the pianoforte. The school enjoyed spacious and well laid out grounds, with a grotto, an interesting collection of fossils and an aviary of ring doves. A large coach house was available as a play room on wet days. Frequent excursions were made to nearby places of interest and occasional entertainments were held in the garden to develop the pupils’ musical and elocutionary abilities.

Nearby was Southgate House School, where the Primary Care Trust is situated now. A school there was run by Mrs and Miss Cunnington, who took junior boys and girls. Advertisements for the school drew attention to the pleasant grounds and kitchen garden, and the sanitation was described as ‘perfect’. The curriculum was unusual, with drill by Sergeant Smith, fencing and woodwork. Instruction on gardening was given by ‘ a certficated lady from Swanley Horticultural College and needlework was ‘systematically taught’. A High Class School for girls was advertised at Brownston House in New Park Street for resident and non-resident pupils, run by Miss Bidwell.

There were two private schools in the Market Place- Parnella House and 14, the Market Place. Parnella House was started in 1870 at 14 Long Street by Miss Davies and in 1896 she was joined by Miss Ward; they then moved to 26, the Market Place and later to 23 , Parnella House in 1907. In their advertisements, they drew attention to the ‘large airy schoolrooms overlooking a pleasant garden,’ ‘careful tuition with home comforts and liberal table’, ‘music a speciality’ and ‘special attention to backward and delicate children’. Harold Bailey was a pupil there and he was the first University of Australia student to become a Professor. From 1936 to 1967 he was Professor of Sanskrit at Cambridge University and was knighted for his services to Oriental Studies in 1960.

The normal school day at Parnella House began with prayers, then reciting the alphabet. Slates and slate pencils were provided with a sponge to rub out, though pupils often preferred to use spit. Sums were done on squared paper and writing consisted of practising pot hooks. Needlework cards had holes to join up with coloured thread. The older pupils wore a uniform, the younger ones had blue and silver sew on badges with the initials PHS. On the retirement of Miss Davies, the school was taken over by Miss Ethel Springford, who in 1932 moved the school to 45 Long Street and in the late 1930s the school was taken over by Miss Kate Fudge

The other school in the Market Place was Devizes College, run by Miss Ada Bennett at 14 the Market Place, which had started at 19, Long Street and then moved to Barford House in St John’s Street. Stress here was laid on preparing boys for public schools, professional examinations or a commercial career. Ada Bennett stated that her aim was to turn out men and women capable of holding their own in after life and maintained that this is attained by careful training and tuition rather than by cramming for exams. The college boasted a gymnasium and a carpenter’s shop and a 4 acre playing field was a short distance away, where annual sports were held. The girls’ department was known as Castle Grounds School and their entrance was in the Market Place, along with that of the kindergarten, but the boys entered in Station Road, so there was evidently some segregation. The boys must have been very conspicuous in their scarlet caps. In a review of the school in The Pictorial Record in 1900, the Principal claimed that ‘the well educated woman must be thoroughly informed without being a blue stocking, well versed in outdoor pursuits without being in the least degree mannish, self reliant and resourceful, while at the same time ladylike’. The curriculum was extensive and included class singing and harmony, swimming, gymnastics, history, geography, religious instruction, with extras such as violin, piano, fencing, dancing and bicycle riding ‘conducted under the most careful supervision’. The staff was highly qualified, with visiting mistresses. Elsewhere in the town, schools existed at 18, Long Street, 29, St John’s Street, 24 and 27 Bridewell Street, 3, Northgate Street, and 16, The Market Place, John Kent’s House.

In the late nineteenth century, secondary education was being developed by local councils under the Technical Instruction Act and in 1902 the Balfour Education Act abolished the elementary school boards set up by the Education Act of 1870 and made county councils the local authority for secondary and technical education. They could levy rates to support such schools on a non-denominational basis. As a result of this Act, Devizes Grammar School opened in 1906 on the Bath Road, so taking many of the pupils who had been previously educated at private schools. In 1924 Wiltshire County Council purchased Southbroom House for educating children over the age of 8 and the new senior school was opened in 1926, Heathcote House being bought as the headmaster’s house. So the raison d’etre for private schools was being eroded.

What then had these private schools achieved?

They obviously varied in the type and quality of education they provided and the picture painted by Charles Dickens in Nicholas Nickleby of Dotheboys Hall was a caricature, but they inevitably helped to perpetuate the class structure. Children attending the church or nonconformist schools would leave at the age of 10 or 12 to go to work to contribute to the family income, but middle class parents who were ambitious for their children were prepared to pay the fees to keep their sons and daughters at school until their teens to equip them with skills for a career in commerce and the professions. Girls, though, had limited career opportunities and, for many, marriage to a respectable man was the ultimate aim, with all the security that provided. Accomplishments rather than learning leading to a career were still the aim of girls’ private education. It was not until the 20th century emancipation of women through being given the vote and the education of women at university level that they acquired greater career opportunities, for which I am personally gratefully. I will end by showing you some of the books which may have been used in these schools and which we have in our Library.

.